A Player’s Guide To Spring Training, Pt. 3: PitchingEmily Nemens

Throw a perfect game.

Throw a no hitter, three walks or less.

Throw a no hitter through seven.

Throw a two-hitter into the fifth.

Make it out of three in one piece.

Listen to your catcher, he’ll talk you down from most any ledge. Unless he wants you out as much as the next guy, in which case it really is time to go. Thank your catcher for his honesty.

Forget about that inning you saw every batter once, the 4-5-6 guys twice, the other team licking their chops like barracudas, like stirred-up rattlers, like spoiled, sinister lap dogs named Candi and Mitzi and Kirby Puckett. Forget about it enough that you can sleep tonight without tossing like a boxer getting bounced around the ropes, a guy more down than up.

You are up. Visualize how up you are.

Throw a ball he could hit, but doesn’t. Relish the sound of the whiff, the humph of an ump making his strike noise, the polite clap from the wives’ section.

Throw one hundred miles per hour, fastballs so fast the shortstop slaps you on the ass at the end of the inning.

Throw sixty-five miles per hour, but put some knuckle on it, flatten the ball so it loops like a drunk and flying squirrel. You too will be confused by its trajectory, but act like you aren’t. Acting is half of everything.

Buy your catcher all the beers. Buy him all the burgers, add cheese and guacamole. Pay for the dirty channel in his hotel. That guy’s giving up his knees for you.

Never, ever say your wing hurts.

Don’t wince and rub your shoulder. Don’t grimace and massage your elbow. Don’t frown and press your thumb between the bones of your hand. When you’re on the mound, don’t make any faces at all, and don’t ever fucking touch your wing.

Be nice to the team’s special-trainer guy. Get all the wraps and gels and slings. Get the best rub downs you’ve ever had, better than the ones from your college girlfriend, the most determined, awkward woman you’ll ever love. Better than the one from your pop after you threw your first win in little league, than the one from your mom after you threw your first loss. Every other loss, too, until you were too tall or proud to let her touch your shoulders.

Get promised a starting spot on the five-man rotation, or on AAA’s list, even on double’s. Fuck, take a spot on the single-A affiliate, a little team in Idaho that’s mostly just boys too young to drink, which makes them drink harder.

Don’t show your disappointment when you’re sent to the pen. There’s worse things than relief.

Find a spot where you’re not sitting in anybody else’s spot, where you can hear the other guys well enough to answer their questions, even the ones they ask when they’re not looking at you, even the ones that sound snide or sarcastic. This, too, is a ritual.

Wake up early at the cheap hotel, shower, look at yourself standing naked in the bathroom mirror. Repeat: I’m a pitcher. I’m a pitcher. I am a pitcher. Then suit up, go to the ballpark, and spend the day waiting for the chance to prove it’s true.

image: Andrew Weatherhead

A really good sports play

Mark Baumer

This is a really good sports play. It involves only one player. He or she will get the ball/baton/puck/flag/thing in the middle of the field/court/stadium/universe. The player will not move and continue holding the thing they were told to hold. The opposing players will respect the player’s decision to not move and will vacate the field/court/stadium/universe. The player will continue not moving until the thing they are holding and the location where they are holding it no longer exists. Most likely the player will also no longer exist which is ideal, but not necessary for this really good sports play to be successful.

Wrangler Dave Housley

“I thought you were going to play football,” she says.

“Yeah,” I say.

“You’re wearing jeans.”

“Yes.”

She is folding laundry, matching socks. She rolls a pair into a neat ball and drops them into the basket. Even for this, she has a system. She has equipment – a thirty dollar “Laundry Pal” from Crate and Barrel. She rolls and drops, rolls and drops.

I pull up my pants and reach into the Sears bag for the new socks – black, UnderArmour. I noticed this last week. He wears the jeans, and then athletic socks and the Nikes. But the socks are black, so they go better with the jeans. I had just normal socks on last week, the white ones like we wore in high school basketball. I had it wrong.

“Wait,” she says. “I’ve never seen those jeans before. Those are like Mom jeans. Those are like Eighties jeans.”

I can feel the heat rising to my cheeks. My forehead sweats. I look at the socks, take a deep breath. Do I want to get in a fight? I glance at the clock radio. It’s 2:30 and it will take twenty minutes to get over to the athletic fields. Game starts in an hour. Last week he didn’t arrive until right around three, a half-hour early, making some joke about old habits dying hard. This week, he could be there earlier. He could be there right now, standing around, wondering why there’s nobody to throw to.

I decide to go the direct route. “You know what these are, Sally,” I say.

“Really?” she says. There’s a little bit of laughter in her voice, a little bit of pity. “Those are Wranglers?”

I nod.

“Turn around,” she says.

I feel ridiculous but I do it.

“Huh,” she says. “They took that W thing off them. But those are Wranglers alright.”

There are a million things I could say, like how can you notice one pair of new jeans but not when I shaved my mustache or when I lost twelve pounds on that South Beach Diet, like how can somebody who buys hundred dollar jeans six at a time on the internet make any comments about anybody else’s jeans. I remember what the marriage counselor said.

“Yep,” I say. “Wranglers allright.”

I put on the new sneakers. Cross Trainers. Nike. Almost the exact kind that Dale Junior wears when he comes out. Close to the same kind, but not too close. It’s tricky. It’s a line we’re all trying to walk. It’s nothing we would ever talk about, not ever, but I see the rest of the guys doing the same thing, all of us slowly picking up on it, morphing, figuring it out -- Wranglers and Nikes and black UnderArmour socks and dark green and mustard colors.

You can take it too far, though. Last week, Earl Tucker from the Legion had on the exact same non-branded, Packers-colored shirt that Brett had on the week before. The same one. I wanted to ask if he had Googled it, or just got lucky at the Sears. It was too much, though, a step over that line. Brett would never say anything, but he didn’t throw a single ball Tucker’s way all afternoon, and when we were hanging out by the pick-ups afterwards, Brett and Dale joshing and slapping each other on the shoulders and the cameras getting every moment of it, Tucker was not asked to “come on over and have a few.”

Sally finishes with the socks and starts in on her underwear – white cotton, sensible, the kind you picture on your mother but not your wife. She folds each one the same way, right over the center, left over the center, bottom over top, and into the Laundry Pal for the five step trip to the dresser.

“Do they all wear those?” she says. “To play in, I mean? You do, like, play football?” She’s trying to be neutral, to really ask the question, show interest. This is a thing from the marriage counselor and she’s not very good at it, but I appreciate it so much I want to cry or punch the television.

What did the counselor say? Communicate. Be honest. Be friends again, then let the lovers part come back naturally. She said all that and then she wrote the prescription for the little blue pills and asked about the co-pay.

“Well it’s not really a real game,” I say. “I mean, it is a real game, but…” How can I explain it so she’ll understand? Do I want her to understand? Do I want to think about it enough, even, to be able to explain to somebody else?

I stand and take the belt out of the Sears bag. This is another thing I had wrong. You don’t wear your work belt to play football on Sunday afternoon with Brett Favre and Dale Earnhardt, Junior. I feel like maybe somebody should have told me that, but the main rule seems to be that we don’t talk about it any more than to say something like, “you coming out Sunday?” Like any of us would miss it. Like we’re not counting days until we can be out there again. Like we’re not holding our breath hoping he doesn’t lose interest or get signed by some playoff team with a gimpy quarterback and then what would Sundays be again but the day before we slog back to work?

“But it’s football,” she says. “In jeans?”

Communicate. Be honest. Be friends again. “Yeah,” I say. “They do all wear them. Dale Junior, too, when he comes. It’s not bad. I mean, if you do get tackled or you fall down or something, you know, there’s enough fabric there to…” I feel like I’m ten years old, trying to explain Batman to a grown-up.

“You don’t have to make it make sense, Tom.” She says it softly, puts a hand on my arm. “I get it.”

I squeeze Sally’s hand. It’s warm and a little moist. She smells like Fabreeze. “Thanks,” I say. I want to tell her everything, how effortless it looks when he throws the ball, how amazing it feels to catch one of those spirals, what it’s like after we play, when we’re leaning against the trucks and cracking jokes, listening to Brett tell stories about Lambeau Field or the Super Bowl, how it feels like we’re in the center of the world all of the sudden, like the cameras amplify everything – the jokes, the game, the jeans, the Nikes, even my own little life. I want to say all of that but it’s getting late and Sally has moved on to her jeans and I picture him there, standing next to the pickup with a bag full of footballs and wondering why he even bothers with this shitty little town and us assistant managers and sales reps and teachers and accountants.

“Hey,” I say, “I really gotta get going.”

image: Aaron Burch

The Business of WaitingAlex Streiff

We go to the golf course with a case of Busch and two deep-sea fishing rods fitted with steel leaders. We go at night, the high beams of the jeep shining over the water. It shimmers and shakes with every little breeze. It explodes like a broken windshield with every fish that jumps. We cast out lines with chicken legs skewered on big hooks. The waiting is the best part. Sounds of bullfrogs, sounds of bugs. My father asks me, Whatever happened to that girl? Why don’t you call your mother anymore? Dad uses the gators to make boots, belts, whatever people are looking for. He eats the meat. You have to wait until it swallows. Snare the dinosaur inside his fucking gut. That’s why I like the waiting best. Bellows of bullfrogs to their mates. He keeps a .357 magnum in a shoulder holster to finish the job. He reels them in writhing, confused.Fucking slow night, he says. We drink the beers, wish there were more when they are gone and complain about it until the sun comes up, and we are drunk in the sunrise.

image: Andrew Weatherhead

SaturdayKara Vernor

Girls, sweating in their polyester knickers, await their turns at the plate. Ankles clacking, mouths breathing, “We want a pitcher, not a belly-itcher!” Coach Agliolo frowns.

Bench 1 watches, blows a bubble that snaps, licks the film from her upper lip. She leans to Bench 2 to send a secret down the line: “She’s throwing high.” By the end, “Sheila bought a thigh.” “She bought a what?” End says, her training bra itching like catcher’s armor, a Sunday dress. At home her Barbie sits sideways in a box of toys, longing to bake a cake and press up against Ken.

Two outs, and On Deck becomes At Bat. She steps to the plate, raises her club, thinks Rover is coming over. Boys from her school play two fields away, as distant as taxes.

The pitch comes high, and she can’t resist, her discipline shot by Monday through Friday. The pop-fly arcs toward the shortstop, and the team is up, clutching the chain link, screaming despite the odds, “Run! Run!”

The ball lands in leather and the groan is collective. Heads down, the girls scurry for their mitts, rush the field to take their places, their rightful places.

Floppy SocksMatt Mitchell

has anything ever been more intimate

than becoming stretched out

around the ankle of a jumping leg,

as if a body only knows how to fit

when it sags beneath

what we haven’t touched in so long.

I am undone by all of the ways

there is no light inside the parts of me

still shrinking.

by how one person can predict

their own death unintentionally.

like Pistol saying

I hope I don’t play in the NBA for 10 years

and then die from a heart attack at 40

and then doing just that.

they make airplane parts from titanium hips

knocked loose out of cremated bodies;

my doctor says I am at an increased risk

for strokes while on testosterone

just to maybe have a kid

who’ll grow up to look like me.

how are we ever supposed to disappear

gracefully

when there’ll always be someone left

who still recognizes the hole

in the sky that gets left behind,

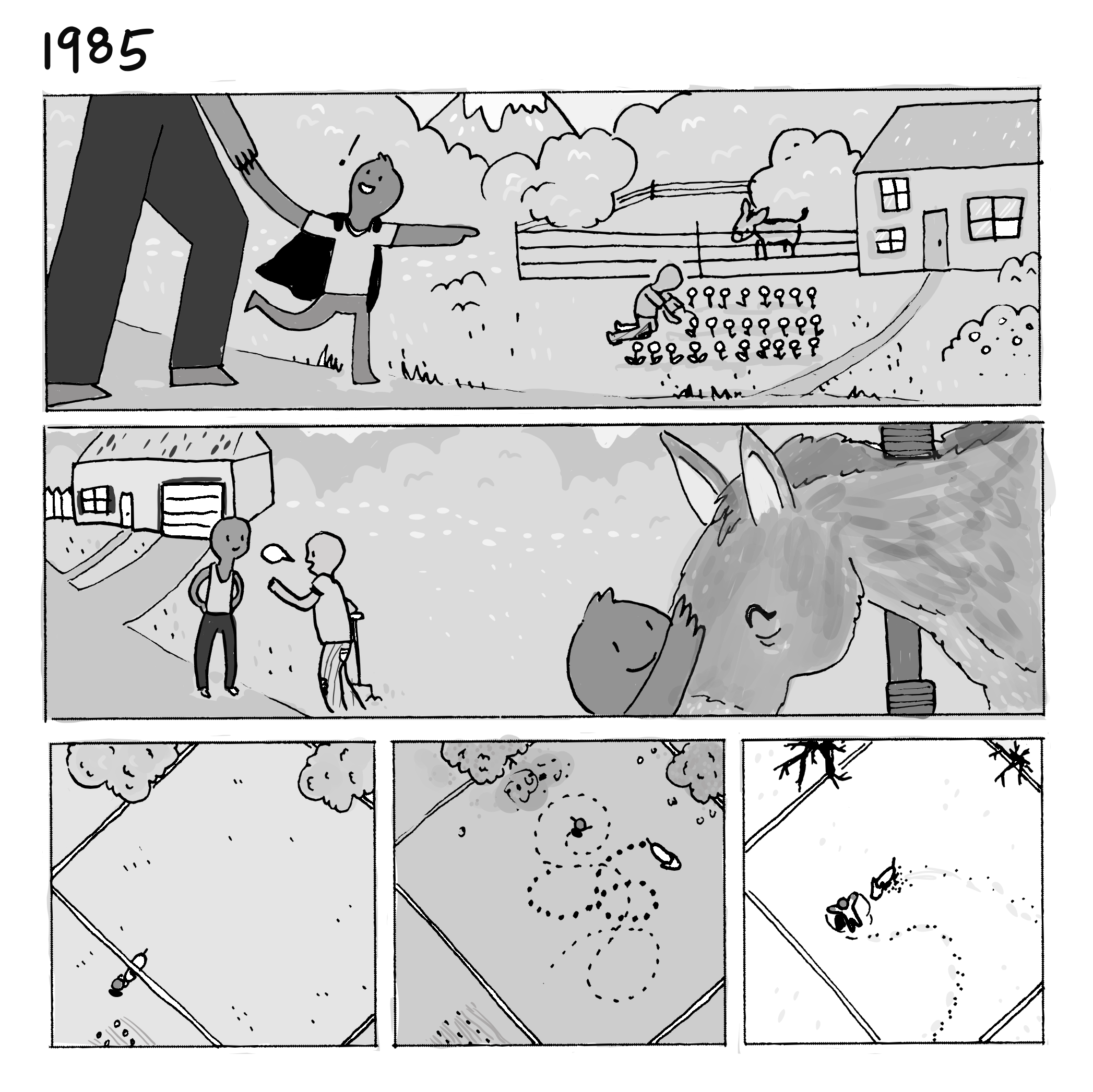

Carl “The Monolith” Reinhardt TJ Fuller

I used to part masses. To wade through throngs of children cheering. Boogie would press play on the cassette, and I’d come through the crowd instead of take the aisle. I’d roll on the trampoline and stand above a field of pumping fists. We didn’t have to recruit fans from the arcade or playground. We didn’t cancel matches because the audience was the rest of the card. After a victory, I could surf kids back to the garage. But nothing’s what it used to be.

Today, I’m supposed to job to some oboe player. With him come women, two basics, and a boy who sits through my entire entrance anthem. My cousin, Charlie, brought some dude who vapes, and my neighbors are out on their porch. Most of the yard is aisle.

I know what people say. Backyard wrestling’s bullshit. The matches are fixed and the cuts are scheduled—or maybe they think we’re all psychos, motherless hooligans smashing our bones against each other in the hope of feeling something again. All that’s true, and more. Charlie’s divorce wrung him out. It ruined his relationship with every decent joint in the city, except my backyard. Boogie’s little girl has leukemia—he can’t ever quit that khaki soul-suck with benefits. He needs the sun on his powerbombs, fresh air and a hip-toss. I still come to be famous.

I high five my cousin, bounce a few times on the trampoline, and climb down to let the one from the wind ensemble enter.

At first, I beat the couch cushions in my mother’s basement. As “The Death-Defying Reinhardt,” the outfits I imagined changed depending on the latest movies I’d seen or comic books I’d read. The stools from the bar stood as corners of the ring and old campaign lawn signs were unforgiving steel chairs.

Then at fifteen, we started the Willow Bluff Wrestling Federation. I broke refrigerator boxes over Boogie’s head. He mashed my back against his chainlink. The bloodier the shows, the more kids showed, football players and tabletop gamers and theater girls. We fashioned a championship belt out of a dead lifter’s leather strap. I still have it in my wife’s closet.

Oboe does two backflips and shows off his splits. Boogie rings the bell.

We bounce a bit, arm bar, trade backhands across our chests. He whispers for me to take a shoulder breaker, so I sell it and yelp. He returns the favor with two legdrops. The boy has his face in his phone, the sun cooks the trampoline’s black mat, and my ankle is still sore from turning it two weeks ago.

The best show we ever had was Boogie’s return from a broken arm. We bought two card tables to toss each other through and packed the grass with the rest of the graduating seniors. We each promised to take one fall. But Boogie got enough gasps after the first one, he told me to double up.

I looked at the crowd and held up a finger. “One more?”

“One more,” they chanted.

The second table sliced Boogie from belt to shoulder blade. We called the match and the football players grumbled their way back to their parents’ cars. Boogie apologized. “My back wasn’t straight,” he said. We thought we’d blown the federation’s chances. Just the opposite. Boogie was legend in that school afterward, and the masses made their way to every match until we graduated. I could see us, in a year or two, in the stadium’s spots, standing above acres of fists.

Oboe loves the air too much, the high bounce or being tossed. Hipshot, phones out, his women feign interest. I take our match to the grass and time a foot with each fist so the blow resonates. I toss him at the ground, crab lock him against the dirt, and stare at his fans.

My one match under the lights was at Knights of Columbus. Some club for grandfathers with the odd card or metal show. But my opponent was a stubborn cockbag. He kept reversing shit I was going to land or ignoring my spots completely. He threw ‘em stiff too, hammers on my back, boots to my shins.

A few minutes in, we both stopped selling. I pulled out some of his hair so he grabbed a chair from the crowd. The ref disqualified him and neither of us got a call for the next show. Boogie bought us tickets but I told him I wouldn’t support the local organizers if they couldn’t tell the difference between the dick who started it and the dick who just couldn’t take it anymore.

Oboe’s fans worry. He tries to press up out of the lock— yanks up the grass I’ve let overgrow—but I pull the hold tighter. His women squat to keep eye contact, clap and call his name. Even the boy. He’s cupping his mouth to cheer.

My wife is tired. She checks the bank’s site each day to make sure we don’t overdraft and watches online videos so she can wrap my sprains and stitch the small cuts. I try not to bother her at night because the television is on and those are her dreams. She jokes about picking up a second job. She won’t ever come to my matches. But I tell her the truth, “I can’t imagine my life without it.”

“Without limping around the house? Without spending so much money on painkillers?”

“What else matters?”

She looks at me like the answer is obvious. But I suck shit at lying.

I let him reverse the lock and once up, he throws a few stiff shots. He drives my head twice at the dirt and I brace with my elbows. His fans howl, hungry for bruises, and Oboe calls for weapons from them. He breaks a lip gloss on my skull, a compact. He grinds the zipper of the boy’s backpack against my forehead.

When the skin breaks, I nurse it a bit, make a mess of my face. Oboe crows. He pulls back my hair so his fans can stare at all the blood and rolls me back on the trampoline. He begins bouncing again.

I know what everyone says. You’re too old, too fat. Too slow to ever be more than a heel in your own backyard.

His fans close in. The boy grabs the ring’s curtain and yells insults—my hairline, man-boobs. I smile, blood staining my teeth. Oboe turns my weak ankle, the tendons wail, but the boy stabs the air with his finger, spittle and curses soaring off his lips.

Who cares if there’s crowds?

I kip up to get caught in Oboe’s finisher—which defies physics, would never flip a man my size. But I sell the hell out of it. I pitch, bounce, and spread my limbs like I’ve fallen stories. He stands and flexes above me, one foot on my stomach, while Boogie counts me out.

image: Michael Worful

The Art of Skateboardingan interview with Kyle Beachy

HOBART: For context, I’m going to start broad: can you cite one quote about skateboarding (about skating, or by a skater) that could be applied to writing? Or your own favorite sentence or passage about skating? Or, kinda converse to the first question, a fave fiction passage or some writing about writing that makes you think of skating? (Feel free to choose just one of those; or if you're really inclined, answer all three; or find some way to intersect those different questions into one.)

Beachy: A photographer named Craig Stecyk covered the early Dogtown days in broadly grandiose language that aimed to define skateboarding as an act much closer to art than sport. "Two hundred years of American technology has unwittingly created a massive cement playground of unlimited potential," he wrote. "But it was the minds of 11-year-olds that could see that potential."

We could call this the Spike Jonze phenomenon, which focuses on the slightly off-kilter way that skaters process and react to the objective world. And it’s true enough, but skaters themselves tend not to think about what they're actually doing when they skateboard. Because they can't -- the activity is difficult and risky and can be the source of great dissonance if it reaches the point of cognition. Here's Mike Carroll, coming back from injury, in the intro to his part in Modus Operandi:

I think about what is this crack gonna do. Okay, what if I don't get my foot on in this position? Am I gonna hit my shin first, or how am I gonna fall? And where am I gonna have to put my hand to break myself from the fall. And then what if I hit my tooth out on that corner right there?

Skaters are simple by necessity. Marty Murawski recently told me that his strategy when he goes out skating is to "do something that the little kid version of me would clap for." Which totally capsizes what for me is the paralyzing part of fiction writing, constant self-evaluation.

HOBART: OK. Quick clarification: Is what's implicit here that Carroll is thinking these thoughts because he's coming back from an injury, and this overthinking is now... making him a lesser skater? I’m asuming he didn’t think like this before? As a skater, what do you (and others) think/how do you respond when you hear this line of thinking?

Beachy: Well, I cut that quote off early. The intro to this video part of his actually ends with Carroll's speech laid over this grainy footage of him rolling up to a handrail, skidding to an exasperated stop and throwing out his hands, all frustrated. "It's a little bitch-ass excuse," he says, "but whatever."

Skateboarding is terrible for the human body. There is no way to spin it as a healthy or wise activity. Injuries are unavoidable, and each one has the potential to cast a wide, dark pall of doubt over a skater's confidence. We all know that it’s a stupid thing to do. Carroll's is a common response: in order to power the body through the nauseous fact of what can and does frequently go wrong during any trick, you’ve got to get your head right, which means, essentially, turning it off.

And so the "little bitch-ass excuse," a weakness to overcome by way of "whatever." Stop thinking. You'll hear a lot of "bitch" and "pussy" among skaters, which I won’t defend. But it is indeed a kind of war, which is essentially the body trying to beat the mind into a kind of mute stupor (it's not uncommon to see a skater punch himself in the head), and is of course completely unnatural. We're attempting to shut down the basic preference toward preservation that our bodies evolved over millennia. As you can imagine, this task gets progressively harder as you get older and shed that idiot confidence of the teen years. The mind gets louder.

HOBART: That makes sense. Getting back to Murawski saying his goal is to “do something that the little kid version of me would clap for." As I was reading, I got all excited -- “yes! both in my own writing and with Hobart” my (albeit usually unstated) goal is often just to do something I myself would find rad. But then you come in and sweep the legs out and say that is the “paralyzing” part for you, which makes sense, too, but also reminds me of many of my own writing frustrations (difficulties at turning off inner editor, etc.).

Beachy: I tried to get at this issue in an essay for the The Chicagoan. After I read The Pale King I decided to drive to Peoria, IL, with my skateboard. I found two skateparks there and both were very dumb. So I drove around Peoria Illinois and thought about boredom and fun and unfinished manuscripts, and eventually ended up downtown along the river as the sun was setting and one of our gorgeously brutal thunderstorms was rolling unstoppably in from the east. I'd come hoping to use skateboarding, which is the most fun thing I know, to reframe my approach to fiction writing. The storm was a convenient metaphor. What happened, technically speaking, was that I ate shit. Then it started raining very hard.

And still it was fun. So my point is that the really vital common denominator between writing and skateboarding isn't creation, or reinterpretation, or translation of the world. It is failure. What the activities have in common is the blood they draw, or at least should draw if we're doing them right.

HOBART: It seems like some of what I'm reading in the above (or at least what I'm trying to read into it, in part trying to summarize and synthesize your answer and probably part laying my own thoughts overtop it...) is that skateboarding is best (most fun? most innovative? most pure?) when you're not thinking about it but just doing, a kind of instinctual action and pure subconscious.

One, do you think that's true, to some degree, or am trying too hard to read it through my own lens? (Or some of both?)

And, second, with your anecdote about Peoria, I wonder if some part of the reason you "ate shit" was because you were trying too hard to force epiphany? Which leads me to wondering if failure isn't the only common denominator between writing and skateboarding, but if they also share some kind of... beauty through non-thought? I mean, both require endless practice, and both certainly do require plenty of thought, but I wonder if they don't also tap some kind of similar perfection through subconscious when, for a moment, everything else is washed away?

Beachy: Go back to that example Mike Carroll trying to ollie over the handrail down those stairs. The first wave of doubt comes during the approach, as you're rolling up to the stairs – you either convince yourself to ollie, which is dangerous, or abort the attempt by skidding or turning away, which is safe but, per Carroll, crazy-making.

The second wave occurs once you're airborne, and when it comes there are once again two prevailing options. The first is trying to land, which is dangerous because any slight misalignment of weight distribution or feet location will lead to your body being thrown and abraded by the street, or you roll an ankle or crack open your fragile little human skull, or whatever. Landing wrong means hurting. You can imagine how this gets more complicated when you're flipping or spinning the board as you fly, then catching it with your feet, then landing. The second option when you’re airborne, which is the much "safer" option on a purely instinctual level, is to kick your board out of your way, aborting the attempt, and landing on your feet.

The kind of soft paradox about all this is that injuries are actually more likely when you fall prey to the misguided instincts for the second, "safer" option. You’ll kick away the board and it’ll land weird and pop up and hit you in the face. It happens time after time -- we hurt ourselves the worst, and most stupidly, when we doubt our capacity to just do the trick. Way too often, I'm personally able to equate thinking with doubting. The reason I ate shit in Peoria is that I got spooked and bailed and ended up with an elbow scraped raw. I thought when I shouldn't have.

This is careening toward the realm of self-help, but there's something to it. Writers of course suffer endless tides of doubt. For us, kicking away the board could mean settling for the pat, neatly causal narrative sequence to create meaning. Which we know people like to read. Or repeating the same syntactic patterns that we know we’re comfortable with. Or it could mean aborting the manuscript all together.

And I guess for me what I need to get back to is, yeah, what you’re calling beauty. Doing the thing as thoughtlessly as I can, knowing that there’s a future me who is a relentlessly critical asshole just waiting up there to review the work once it’s done. This is another big thing the two activities have in common -- the first thing a skater wants after landing a trick is to check how it looks on film. It’s a little vain-ass habit, but whatever.

image: Andrew Weatherhead

Ball Don’t LieChloe N. Clark

In my dream last night, basketball was on

and Sheed was a three-point machine, shooting

half-court shots that were nothing

but net. Last year, I told my boyfriend

to watch his step on ice and when

did I get so protective, so quick to keep

everyone safe around me? Sheed was never

a three-point machine but he hit when

he needed to. Sheed was defense and

attitude and tattoos of the sun. On the phone,

I ask a friend if her husband is doing better,

if his dreams have gotten less filled

with terror. She tells me some nights

are better than others. And I think

that aging is often like that: we take

our better where we find it. When

Sheed was a Celtic and in the playoffs

that final year, I saw him clutch

his back, the pain clear on his face

and, I thought, some day, I will

understand this loss.

image: Aaron Alford

Explaining An Affinity For R.A. DickeyLauri Anderson Alford

after A.E. Stallings

That his fingernails are immaculate, shaped

into thin arches of moon. That he files them

in the locker room before games, between innings in the dugout.

That one hangnail can send him to the Disabled List for weeks.

That there is fragility in this, his reliance

on a part of the body that is meant to be torn away.

That he spent years becoming

another kind of player, and that this is necessary

for a knuckleballer, to have spent

those years and then to unspend them,

that the knuckleball requires this doing and undoing

and redoing, and that it chooses for its work

the one who best knows the meaning of revision.

That he cannot know, when he releases the ball, what shape

it will take. That he spends his life in pursuit

of a pitch he cannot ultimately control, which is

a kind of mutual understanding, I think,

between him and his pitch,

a kind of letting go.

That his hand is a claw, his arm a wing. That he is a bird

and so the ball, too, is a bird simply because it is his,

having been clenched in that way, having been pushed

from his body (and never thrown), because it longs for flight,

not speed. That speed is the least of these things.

That the knuckleball never asks for more

than its own release. That it wants to be given

and never given to. Not ligament or joint or nerve.

Not the precarious alignment of bone. It allows him to keep

his arm that it may find its end at the end

of an arc, however slowly, however it drifts,

over and over again—which is like a beginning

if the beginning comes in pieces,

if it comes over time.

harry styles and i meet at the packers game andAlexis Briscuso

it isn’t like a rom-com. i don’t slide into the seat next to him like i belong there, i don’t steal his cup holder with my beer as an excuse to talk to him, i don’t steal his big foam finger and poke it playfully in his face when aaron rodgers does something stupid and we have no choice but to laugh about it, i don’t let him steal the big foam finger back when aaron rodgers inevitably makes up for his stupidity like sports men do and we both scream ourselves hoarse, i don’t say “they’re so fucking cute” to him when shailene woodley runs out on the field after the game-winning touchdown and aaron rodgers gets down on one knee to propose to her and i don’t gasp like everyone else does, i don’t ask him if he sees that too that thing i’m seeing that looks suspiciously like a UFO hovering just over the scoreboard, i don’t velcro to his arm when the spacecraft zooms down like a targeted pass and lands on the field, i don’t lace my fingers into his as we make a run for it while alien life forces gun down the green bay packers and NFL employees and commentators and coaches and water boys with vaporizing rays. i don’t do that. this isn’t a romcom.

no, at the packers game, harry styles sits in a box and we have never met. but i watch him drink beers from my seat four entire sections away, a speck like dust on a map. my eyes, metamorphosizing into microscopes, catch him in the act as aaron rodgers scores. darting out first, a landing pad for the neck of a bottle, an extraterrestrial tongue.

image: Aaron Burch

For the Walk from Jackson Ward to Oregon Hill Allie Hoback

You stole a skateboard on your way to me

the night you came over wasted: the tail end

of a bender though we’d never call it that.

You must’ve cruised down the hill: top

of the Cherry & Albemarle intersection—

sweet wind on drunk cheeks,

& slight drips out the corners

of your eyes from brisk & memory.

All I know is—whatever you hit—

you showed up at my door with a bloody forearm,

then sat on the edge of my bathtub while I kneeled

& poured the peroxide down your arm

we watched it bubble & fizz & turn to pink drips

down the drain & you pressed your forehead into mine,

dried sweat to lotioned skin, & whispered thank you

for taking care of me & I nodded & took you to bed.

In the morning we laughed at how hungover

you were & laughed more when you asked:

when did you get a skateboard?

No No Kevin Maloney

[Dock] Ellis threw a no-hitter on June 12, 1970. He later stated that he accomplished the feat under the influence of LSD. - Wikipedia

Jerry flashes his fingers between his legs: one-two-three, low and outside. I wind up, pitch and a hundred identical baseballs form a line between my fingers and the jewel in the catcher’s mitt. The batter could hit any one of them but he turns into a corkscrew pointing his stick at the sun. The umpire calls a strike or he’s the ghost of my grandfather showing me the graves of our ancestors. We’re playing the Padres which means “father” in Spanish. You can’t fool me; we’re babies running around in circles in the kingdom of God.

I roll the orb between my fingers waiting for the next signal but the jewel’s too bright. I can’t see anything but Jerry’s eyes. They’re the color of the pills I ate. It’s a full count, 3-2, which are numbers in the alphabet. He blinks which means: pitcher’s choice. I throw a curve and Padre swings but the ball’s in the bottom of a well a thousand miles deep in my brain. He didn’t see that coming.

Padre walks away knocking the bat against his cleats. When he looks into the dugout his brethren hang their heads. I got a no-no going but you don’t say “no-no” like you don’t step out of an elevator on the 13th floor.

The next batter is Jimi Hendrix. Jerry flashes two-two-one. That’s our sign for, shut the fuck up and just listen to this genius play the guitar.

What the fuck Jerry? This is baseball. I call him to the mound but he doesn’t hear me because he’s getting Jimi’s autograph. Wait, I should get Jimi’s autograph too. I look for a pen but all I’ve got is this baseball. It’s enormous. How am I supposed to throw this thing? I throw it and it hits the grass about ten feet in front of Jimi Hendrix and stops before it reaches home plate. Everybody looks at me like I’m on drugs. A drop of rain hits my eyeball and I realize I am on drugs. Jerry tosses me the ball and now it’s tiny as a raisin. I don’t even need to wind up; I flick it toward home plate like a marble and it hits Jimi Hendrix on the ankle. He walks to first base playing “Foxy Lady” on a Fender Stratocaster.

What inning is it? How many days did Jesus sit in the desert talking to snakes? My arm has blood in it because my arm’s a snake and snakes are full of blood. The batter’s full of blood too and the umpire is Richard Nixon. I’m afraid he’s going to judge me. All these people are here to judge me and I’m here to be perfect. I got a no-no goin’. I just ate more drugs or maybe I swallowed my gum.

Are you allowed to smoke cigarettes on the pitchers mound? I can’t remember. I look to see if I have any cigarettes and then remember I’m playing baseball. All these people are looking at me wondering why I keep touching my pants looking for cigarettes. You shouldn’t judge people unless you’re on drugs. I’m on drugs and I judge all of you and find you perfect. A no-hitter is when nobody gets to first base off a hit. Second base is feeling under a girl’s shirt when you’re in middle school.

I look around and realize the bases are loaded. I walked two of these people and hit Jimi Hendrix with a raisin. Jerry flashes three fingers. I hope my arm isn’t leaving teeth marks on the ball. I throw it. Padre thinks it’s right over the plate but we fooled him by hiding the ball inside another ball. Richard Nixon pumps his fist like he’s trying to start a lawn mower. Padre gets angry and throws his bat which is the opposite of religious.

My teammates say the inning’s over. I think I swallowed gum because the drugs aren’t stronger. They say only one more inning Dock and I say ‘till what? Mazeroski says, you know and I say, the no-no? and he goes, shhhhh! I keep my arm behind my back because I don’t want it to bite anybody.

In the dugout I put more gum in my mouth. A bat boy runs his fingers fascinated over the wood grain of a bat. Somebody cut down a tree to make that thing. Jerry sits next to me. His fingers are wrapped in shiny tape. He flexes them, unflexes them, flexes them again. What kind of pitch do you throw when your catcher’s fingers look like they just crawled out of the ocean?

The rain picks up. Minnows swim over second base chased by a force darker than baseball. The florescent lights cry out in agony. I’m worried about the ninth. My no-no’s a little boat. A baseball is white, stitched together with red yarn. It’s so heavy. What’s inside this thing?

I close my eyes. Keep talking people, but whatever you do don’t say “no-no.” I’m on a journey here.

image: Killian Czuba

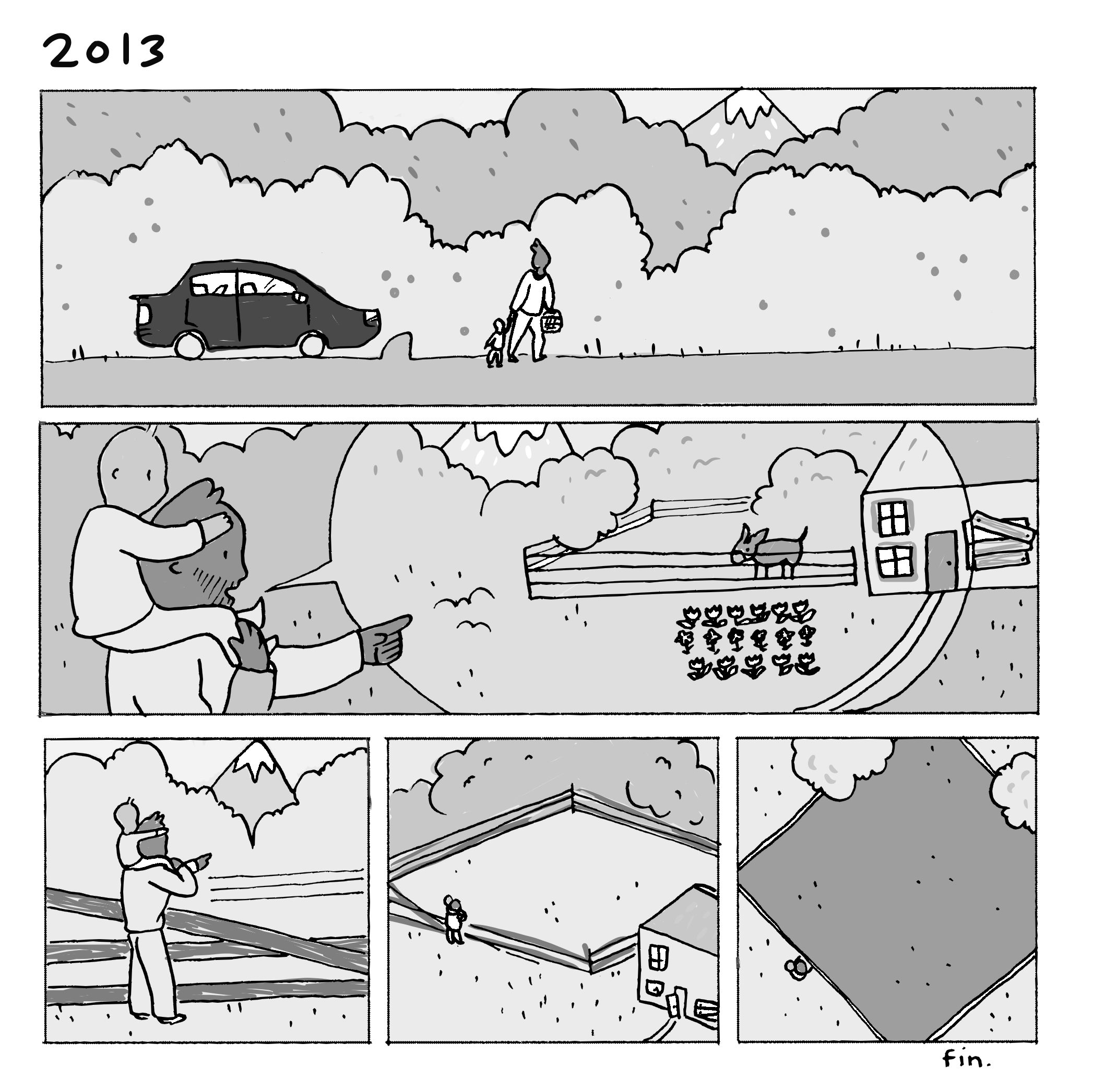

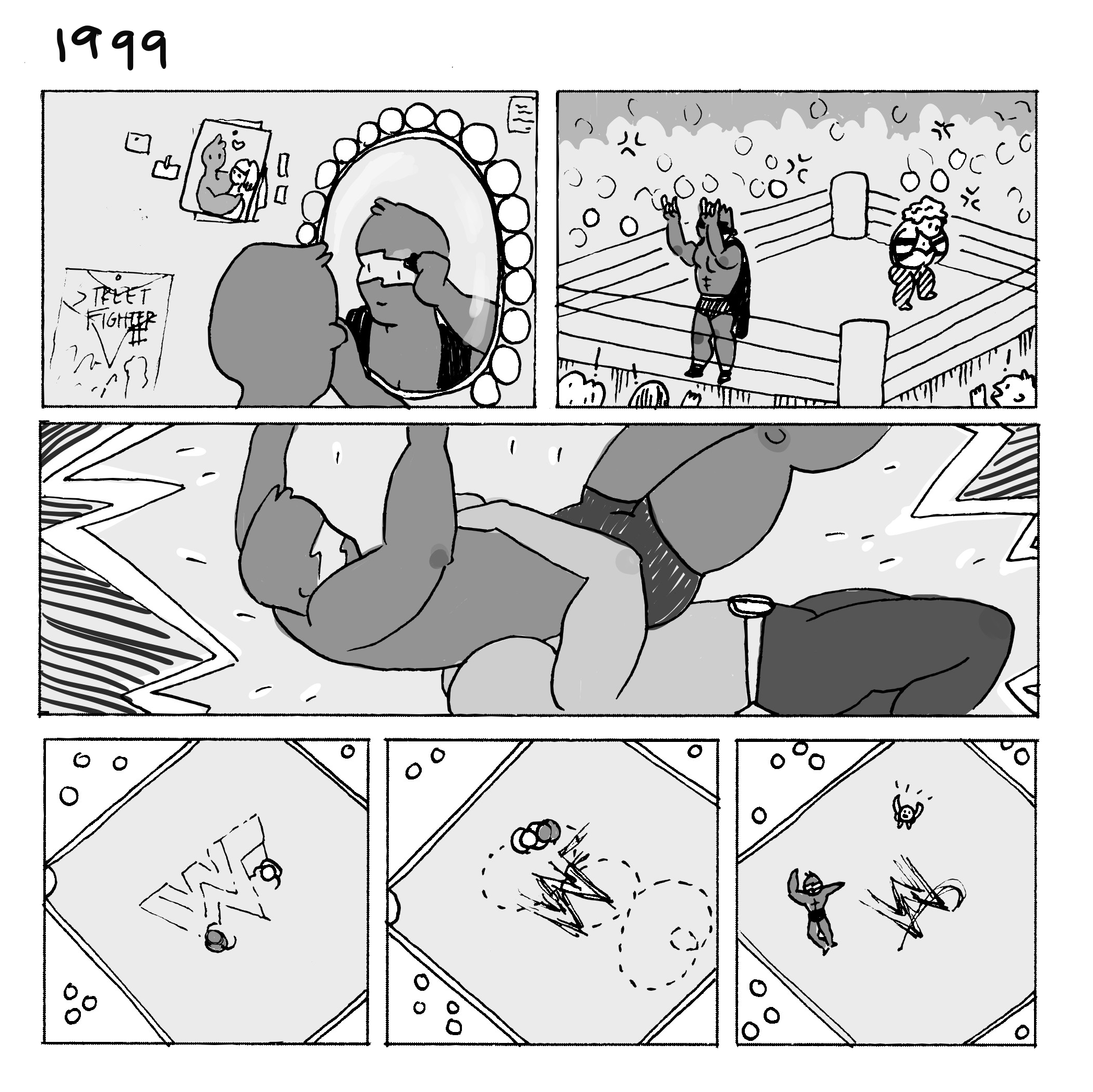

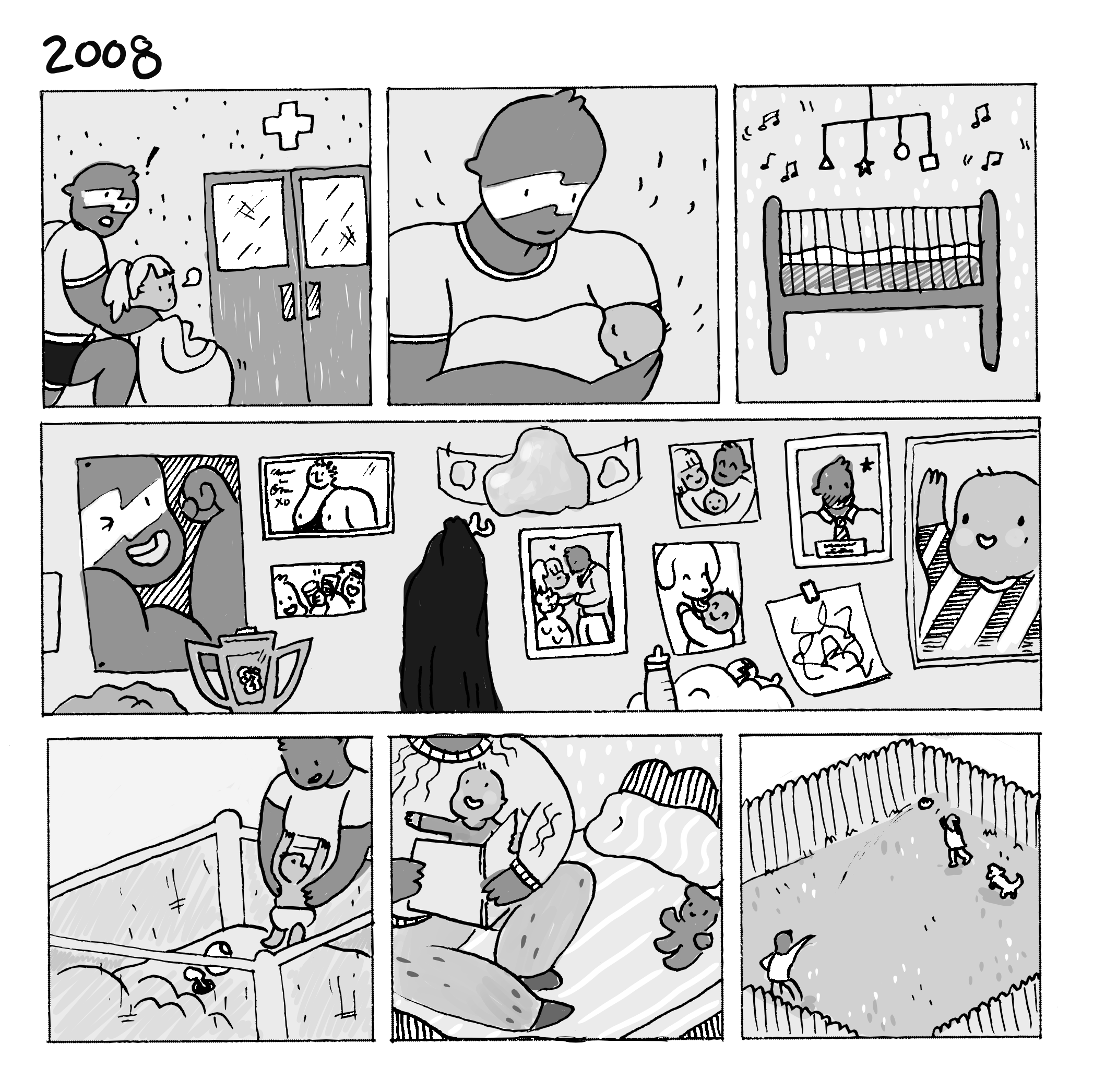

1985

Aaron Burch

Vernon “Ernie” Cervid turned five years old.

By the Chinese zodiac, the Year of the Ox. Ronald Reagan was sworn in for his second term as president.

Coca-Cola changed its formula and released New Coke. “We Are the World” was released to raise money for African famine relief.

The Cervid’s neighbor—the corner house, across the street and at the other end of the block—Mr. Shafer, brought home a goat.

Sally Field, winning Best Actress at the 57th Academy Awards for her role in Places of the Heart, famously exclaimed, “You like me, you really like me!” Only, what she really said was, “The first time I didn’t feel it, but this time I feel it, and I can’t deny the fact that you like you, right now, you like me!” Amadeus won Best Picture.

Down the freeway from the Cervid’s and Shafer’s, in Auburn, WA, a Unabomber bomb that had been sent to Boeing was diffused. Ernie never heard anything about it, though he would have a number of friends over the years whose fathers worked for Boeing. By the end of the year, the owner of a computer store in California would become the Unabomber’s first casualty, though Ernie never heard of that either.

Route 66 was officially decommissioned. Back to the Future was the highest grossing film of the year. The second highest: Rambo: First Blood Part II. Third? Rocky IV.

Ernie, everyday, longed and begged to go down the block to the Shafer’s, to visit and pet Pony the donkey, kept on a leash connected to a wire strung between two trees until Mr. Shafer could build a proper pen. He’d named her Pony as an anniversary gift for his wife, Emma, who’d wanted a pony when she was little. From the time she was Ernie’s age, maybe even.

The first WrestleMania was held at Madison Square Garden.

Live Aid.

Moonlighting debuted. Also: Windows 1.0, the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), and Calvin & Hobbes.

Ernie started Kindergarten. Some days, after school, his parents would let him walk to Mr. Shafer’s on his own, letting him believe in his first act of independence, though they’d carefully watch from the window until Mr. Shafer raised his arm, hello to Ernie, he got here OK to Ernie’s parents.

E.B. White passed away. So, too, Rock Hudson, Orson Welles, Roger Maris, and, mere days after a televised match with Rowdy Roddy Piper, WWF star “Quick Draw” Rick McGraw. The Quick Draw McGraw Show, featuring the anthropomorphic title character horse—red cowboy hat, blue cowboy scarf—aired from 1959-1962. “Tug” McGraw pitched the last game of this career the previous year, September 25, 1984.

Speaking of 1984, that year Ernie’s father, Leonard (Lenny to his friends; Roy to his wife, who liked the sound and simplicity of his middle name, using it at first in jest, and then always, without giving it a second thought, jest becoming the norm) received a promotion and, with it, a substantial pay raise. By ’85, the family talked of moving but, instead, converted the garage into a TV room and added a glassed-in sunroom, with sliding glass doors, onto the back of the house.

New Coke failed and Coca Cola returned to their “original formula.”

Tetris was released in Russia the year before, in 1984, and in the U.S. the year after, in ’86. It didn’t, however, reach its full popularity potential until paired with Nintendo’s Game Boy at the end of the decade.

Ernie would later remember the family decision to stay put instead of move as being related to his personal, boyhood connection to Pony, though that would seem less likely each year he grew older and made his own life and family decisions. He’ll stop short of ever asking his parents, more okay with doubting his memory than the possibility of fully negating the possibility. He’ll also remember Mrs. Shafer as both “Pony’s mom” and as already being gone by the time Pony was brought home, Pony as companion for Mr. Shafter during the depression of post-divorce loneliness.

Cyndi Lauper was queen—she participated in “We Are the World” and won the Grammy for Best New Artist. (She was also nominated for, but didn’t win, both Album and Record of the Year.) She was the musical director for Steven Speilberg’s The Goonies, and made numerous appearances at WWF events, including Wrestlemania, as Wendi Richter’s manager.

(The Goonies was the ninth highest grossing movie of the year. It starred, among others, Corey Feldman, who had been in Gremlins the year before, and would be in Stand By Me the year after, all movies that Ernie was too young to see at the time but would become favorites in later years, Stand By Me especially, Jerry O’Connell’s Vern Tessio convincing him to always be Ernie, never Vern, notwithstanding.)

By the end of the year, Mr. Shafer had moved—the house left vacant, the pen seeming even lonelier than the house itself and also entirely out-of-place without Pony to give it context. Ernie never knew where they moved, what happened to Pony. He’d often wonder, years later, did Mr. Shafer take her with him? Build a new pen? Sell her? What happens to a goat when no longer wanted as a pet?

Mike Tyson knocked out Hector Mercedes in the first round of his first pro fight. Super Punch-Out!! was released as an arcade game. Two years later, Nintendo would release the game for their home system with Mike Tyson’s name attached and his likeness as the World Heavyweight Champion, the final fighter you must fight to beat the game. The special guest referee tag-team of Hulk Hogan and Mr. T against Roddy Piper and Paul Orndoff main event match at that first Wrestlamania was Muhammad Ali. The next year, at only 20, Tyson would break Ali’s record as the youngest boxer to take the title from a reigning heavyweight champion.

Ernie continued to visit even after Mr. Shafer had sold the house and moved—out of habit, forgetting Pony was gone; or hopeful, wanting to visit the empty pen, a place now of sadness but also one of memories of joy. As if the site had become a memorial, church-like, though these weren’t the terms or depth of thought he’d consciously connect to the place until years, decades, later. Until he grew up, moved out and away to college. Until he dropped out of college to wrestle as an amateur, training for the WWF, and then WWE, after the World Wide Fund for Nature sued and the wrestling foundation had to change names and acronyms. Until he spent years perfecting his persona as “the Bison,” in part in honor of his favorite animal, in part after the Street Fighter villain, first introduced to Nintendo in 1992 via Street Fighter II for the Super Nintendo. Until he met Holly in St. Louis, on the road for a match, and they hit it off, dated long distance; until they “gave it a go” and he moved to Missouri for her; until they got engaged, and married, and he finally gave up trying to become a professional wrestler because it was too dangerous, too long of a shot, too much time on the road, away from his wife and home, though Holly was always supportive. Until they had a son, who Ernie immediately wanted to give only the best, wanted to give everything, wanted to recreate the greatest aspects of his own childhood, wanted to build a personal, independent, church-like sanctuary for him to believe in.